The Harvard Gazette | A literary colossus

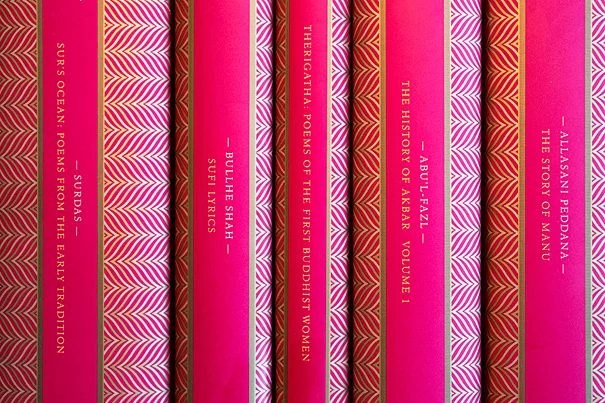

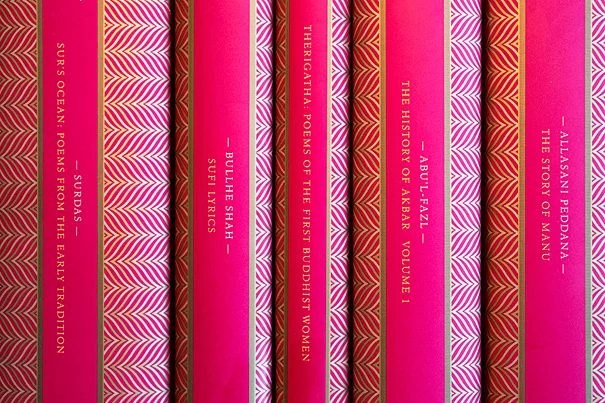

Books Published

In the spring of 2009, Sheldon Pollock ’71, Ph.D. ’75, the Arvind Raghunathan Professor of South Asian Studies at Columbia, was sitting in a Cambridge café with Sharmila Sen ’92, executive editor at large at the Harvard University Press. “I took out the proverbial napkin,” said Pollock. The two sketched out what would be needed to publish his longtime dream: a series of volumes on classical Indian literature.

Why not 500 books over the next century, they thought: poetry, prose, philosophy, and literary criticism — and later science and mathematics? These largely unseen works, some of which date back more than two millennia, had in the last century shrunk to a canon available almost solely in Sanskrit.

… …

Volume 1 of the MCLI, in Panjabi, is “Sufi Lyrics” by Bullhe Shah, an 18th-century practitioner of this mystical poetry tradition. He wrote not long before the British conquest of Panjab in the 1840s, the beginning of a colonial cultural wave that submerged much Indian literature. The verse is pan-religious, and threaded with humor and optimism. “This flower bed of earth is wonderful,” Shah writes in one verse. “Earth goes strutting along, my friend.”

Volume 2 is “The History of Akbar”, the first of seven planned volumes. It’s a grandiose 16th-century rendering in Persian of the life of the Mughal emperor Akbar, who presided over an era of religious tolerance. His bloodline, author Abu’l-Fazl asserts, began with Adam; Akbar’s birth was accompanied by miracles; and his life was suffused with divine light. (“That Akbar is related to the sun,” he wrote, “is obvious.”) This work, a model for historical prose in its day, has appeared in English translation only once.

Volume 3, the most slender, gets a lot of attention for being a translation of what is likely the first collection of women’s writing in the world. “Therigatha: Poems of the First Buddhist Women”, written in the Pali language by elder Buddhist nuns in the fourth century B.C.E., is also the oldest work among the first five volumes.

Volume 4, appearing for the first time in English, is “The Story of Manu” by Allasani Peddana, who called himself the originator of Telugu poetry, though such poetry had existed 500 years before. But Peddana did something new, however. His work is more lyrical and sound-driven, and it recreated Telugu poetry as a private experience instead of a shared public reading. Peddana used prose when verse no longer seemed rich enough, and he was a naturalist in an age when close observation of nature was prized. “They’re rough and fat,” he wrote of wild boars. “You want to know how strong they are? / They bend back thick stalks of bamboo / with their snouts, as if they were flimsy as maize.”

Volume 5, the thickest, is “Sur’s Ocean: Poems from the Early Tradition” in the style of Surdas, the poet laureate of the Braj Bhasha language at the end of the 16th century. Within in less than 100 years, by one account, there were 125,000 such poems, an “ocean” of Sur that one scholar drained to a minimalist canon of about 5,500 works. Four decades in the making, the volume of 433 poems appears here for the first time in English. (Pollock drew on scholarly works done or nearly done for two of the first five MCLI volumes. The others were specially commissioned.)